Snapshot

This commit is contained in:

parent

fa81295a58

commit

5e9ef37813

106

Media/articles/Deep-Sea Mining.md

Normal file

106

Media/articles/Deep-Sea Mining.md

Normal file

@ -0,0 +1,106 @@

|

|||||||

|

---

|

||||||

|

author: Diva Amon

|

||||||

|

link: https://pirg.org/edfund/resources/we-dont-need-deep-sea-mining/

|

||||||

|

done: false

|

||||||

|

date: June 21, 2024

|

||||||

|

image: >-

|

||||||

|

https://publicinterestnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/logo-pirg-c3-US.svg

|

||||||

|

---

|

||||||

|

# We don’t need deep-sea mining

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Relicanthus, Diva Amon and Craig Smith, ABYSSLINE Project, University of Hawaii; Glass sponges, NOAA/OAR/OER, from a 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas; featherstar, Bernard Dupont, CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

---

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The world is moving away from fossil fuels and toward renewable energy from the wind, sun and other sources. Many emerging energy technologies – from wind turbines to electric vehicles – depend on so-called “critical minerals” such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, copper and rare earth elements.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The growing demand for critical minerals is being used to justify **deep-sea mining** – a new form of mining that would jeopardize unique and vital deep-sea ecosystems that science is just beginning to understand as well as the health of the oceans at large.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

**We don’t need deep-sea mining to transition to clean energy.** There are many ways the U.S. and the world can ensure that we have the critical minerals we need without doing lasting damage to the world’s last great wilderness – including by making better use of minerals we have already extracted from the Earth.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

**In fact, the world currently trashes more of some critical minerals in discarded electronic waste each year than would likely be supplied annually by a proposed ramp-up of deep-sea mining in the central Pacific over the next decade.**

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

By building a “circular economy” for critical minerals now – one in which products are built responsibly and to last; fixed when they break; and recycled into new products at the end of their lives – we can reduce the pressure for all forms of mineral extraction, including deep-sea mining, and lay the foundation for a sustainable energy system for decades to come.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### **Why is deep-sea mining so dangerous?**

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The deep ocean seabed is a vibrant, biodiverse place, teeming with complex ecosystems and thousands, possibly millions of species, including deep-sea corals, anemones, sponges and many more that scientists are only now beginning to learn about.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Deep-sea mining operations could take place over hundreds to thousands of square miles of seafloor, harming not only the species that live there, but broader ocean ecosystems as well. The plumes of kicked-up sediment and discharged mining waste from deep-sea mineral extraction could have extensive and wide-ranging impacts on ocean ecosystems – traveling huge distances from mining sites.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Deep-ocean ecosystems are especially vulnerable to the kind of disruption caused by mining the seafloor. Species living in deep-sea environments are frequently long-lived and slow to grow, and previous deep-sea mining trials have shown that areas of seafloor disrupted by mining are slow to recover. In some cases, damage from deep-sea mining could be all but irreversible.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

NOAA | Public Domain

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Recent research indicates that ferromanganese nodules are important breeding grounds for these newly discovered deep-sea octopods nicknamed “Casper,” due to their likeness to the friendly cartoon ghost.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### We don’t need deep-sea mining for the energy transition

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Deep-sea mining is not a potential source of all the critical minerals required for the clean energy transition. Key minerals such as graphite aren’t available on the seafloor at all, and others – such as lithium and rare earth minerals – are available only in limited quantities or in specific areas of the ocean.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Cobalt, nickel and copper are among the minerals believed to be available in the greatest abundance in deep-sea deposits. New designs for electric vehicle batteries, however, are reducing the need for cobalt and nickel, while the amount of copper available in seafloor deposits is just a small fraction of what is available from land-based resources.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

[Analysts](https://impact.economist.com/ocean/sustainable-ocean-economy/dont-buy-the-greenwashing-we-dont-need-deep-sea-mining) [agree](https://www.energy-transitions.org/publications/material-and-resource-energy-transition/) that land-based resources are sufficient to meet future demand for critical minerals for the energy transition. Opening up the deep ocean seafloor to destructive mining is a choice humanity can make. But there are other options – including making sure that we get everything possible out of every pound of minerals we extract from the Earth.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### **How can the “5 Rs” help meet the critical minerals challenge?**

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

America and the world can reduce the amount of critical minerals we need for the energy transition – and do so quickly – by prioritizing the “5 Rs”: the traditional 3 Rs of **reduce**, **reuse**, **recycle**, plus **reimagining** products to last longer and use fewer critical minerals, and **repairing** them when they break.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Analysts ranging from the [International Energy Agency](https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/ee01701d-1d5c-4ba8-9df6-abeeac9de99a/GlobalCriticalMineralsOutlook2024.pdf) to the [Energy Transitions Commission](https://www.energy-transitions.org/publications/material-and-resource-energy-transition/#download-form) agree that these and other “circular economy” strategies can significantly reduce demand for critical minerals over the next decade and beyond. The Energy Transitions Commission found in 2023 that circular economy strategies could **fully close projected supply gaps for copper and nickel, and significantly narrow them for lithium, cobalt and neodymium by 2030.**

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Here are just a few of the ways that the “5 Rs” can help meet the critical minerals challenge:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### **The first step to solving the critical minerals challenge: Stop throwing them away**

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

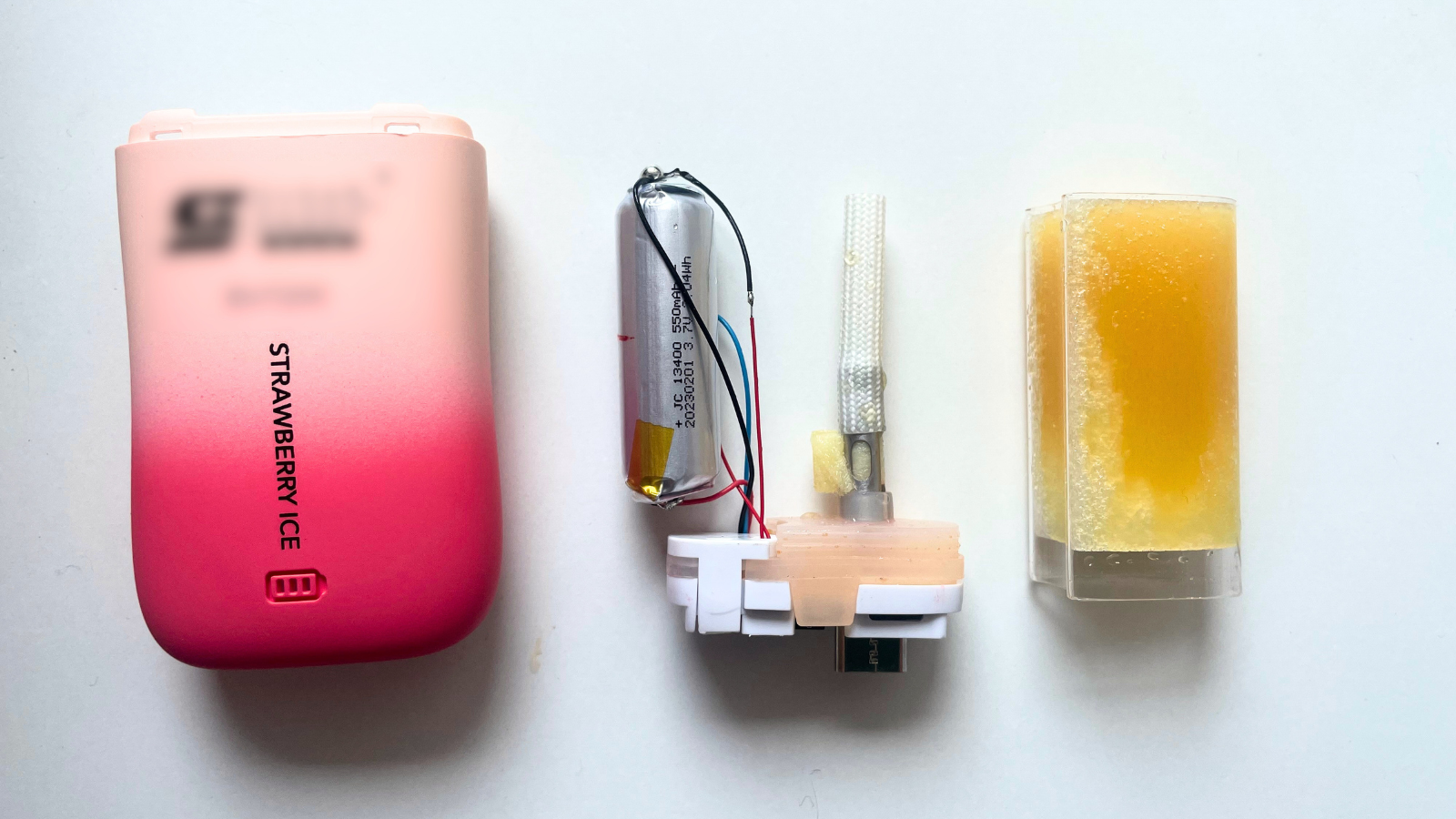

America has a large, homegrown source of critical minerals in the products we use every day – including electronic devices such as smartphones, laptops, earbuds and disposable electronics such as disposable e-cigarettes (“vapes”).

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Many of these electronics have short lifespans – from a few years for smartphones to a few days for disposable vapes. And when they reach the end of their lives, the critical minerals in many of those electronics wind up in our trash. **America produces roughly 47 pounds of [electronic waste](https://api.globalewaste.org/publications/file/297/Global-E-waste-Monitor-2024.pdf) per person each year, with more than 3 million tons of American e-waste going unrecycled annually.**

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Extending the lifetimes of electronics, clean energy technologies and other products throughout our economy can reduce demand for critical minerals at a time of rapidly growing demand. Extending the lifetime of a product by 50% can reduce material needs by as much as a third; doubling a product’s lifetime can reduce material needs by as much as 50%.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

**Federal and state governments should take action to stop deep-sea mining and build a sustainable circular economy for critical minerals.**

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The U.S. Congress should institute a precautionary pause or moratorium on seabed mining in U.S. territorial waters and on processing of minerals obtained by seabed mining in U.S. states or territories. The U.S. should also provide diplomatic support for efforts to adopt a precautionary pause or moratorium on deep-sea minerals production in international waters.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

State and federal governments should adopt “right to repair” legislation to make it easier to fix the stuff we use; ban disposable and irreparable small electronics such as disposable vapes; create standards to help consumers identify more durable and fixable products; and encourage “second-life” applications for clean energy technologies approaching the end of their useful lives.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Governments should invest in improved standards and infrastructure for recycling, especially for e-waste; investigate opportunities for environmentally responsible use of industrial waste streams for critical minerals; and take steps to make every part of our economy more energy efficient and less material intensive.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Governments should improve environmental protections for terrestrial mining; and governments, companies and consumers should advocate for the adoption and enforcement of global standards for environmental and social responsibility in mining.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

---

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

[Stop Selling Disposable Vapes](https://pirg.org/edfund/take-action/stop-selling-disposable-vapes/)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

[Right to repair](https://pirg.org/edfund/topics/right-to-repair/)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

#### Stop Selling Disposable Vapes

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Disposable electronics are terrible for the environment, and that includes disposable electronic cigarettes. Tell retailers to stop selling them.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Sign the petition.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

##### Topics

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

- [Recycling & compost](https://pirg.org/edfund/topics/recycling-compost/)

|

||||||

|

- [Right to repair](https://pirg.org/edfund/topics/right-to-repair/)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

##### Authors

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Kelsey directs Environment Americas national campaigns to protect our oceans. Kelsey lives in Boston, where she enjoys cooking, reading and exploring the city.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Nathan leads U.S. PIRG’s Right to Repair campaign, working to pass legislation that will prevent companies from blocking consumers’ ability to fix their own electronics. Nathan lives in Arlington, Massachusetts, with his wife and two children.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Tony Dutzik is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. His research and ideas on climate, energy and transportation policy have helped shape public policy debates across the U.S., and have earned coverage in media outlets from the New York Times to National Public Radio. A former journalist, Tony lives and works in Boston.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

James Horrox is a policy analyst at Frontier Group, based in Los Angeles. He holds a BA and PhD in politics and has taught at Manchester University, the University of Salford and the Open University in his native UK. He has worked as a freelance academic editor for more than a decade, and before joining Frontier Group in 2019 he spent two years as a prospect researcher in the Public Interest Networks LA office. His writing has been published in various media outlets, books, journals and reference works.

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

##### Find Out More

|

||||||

Loading…

Reference in New Issue

Block a user