The web’s evolution over the last decade has mirrored the American economy. All of the essential indicators are going “up and to the right,” a steady stream of fundamental advances reassure us that there “is progress,” but the actual experience and effects for individuals stagnates or regresses.

The crisis affects platforms, creators, and consumers alike.

_I’m going to try and dissect and diagnose this situation, a bit. You can skip forward if you just want to read my casual, unprofessional pitch for a reboot of the web. The idea is that we could choose a new lightweight markdown format to replace HTML & CSS, split the web into documents and applications, and find performance, accessibility, and fun again._

This post uses the pedantic definition of "the web"Ive discussed attempts to reinvent the "Internet" a few times. Things like dat, IPFS, and arweave are all projects to reinvent an Internet, or a transport and data-sharing layer. The web is what lies on top of that, the HTML, CSS, URLs, JavaScript, browsing experience.

### The platform collapse

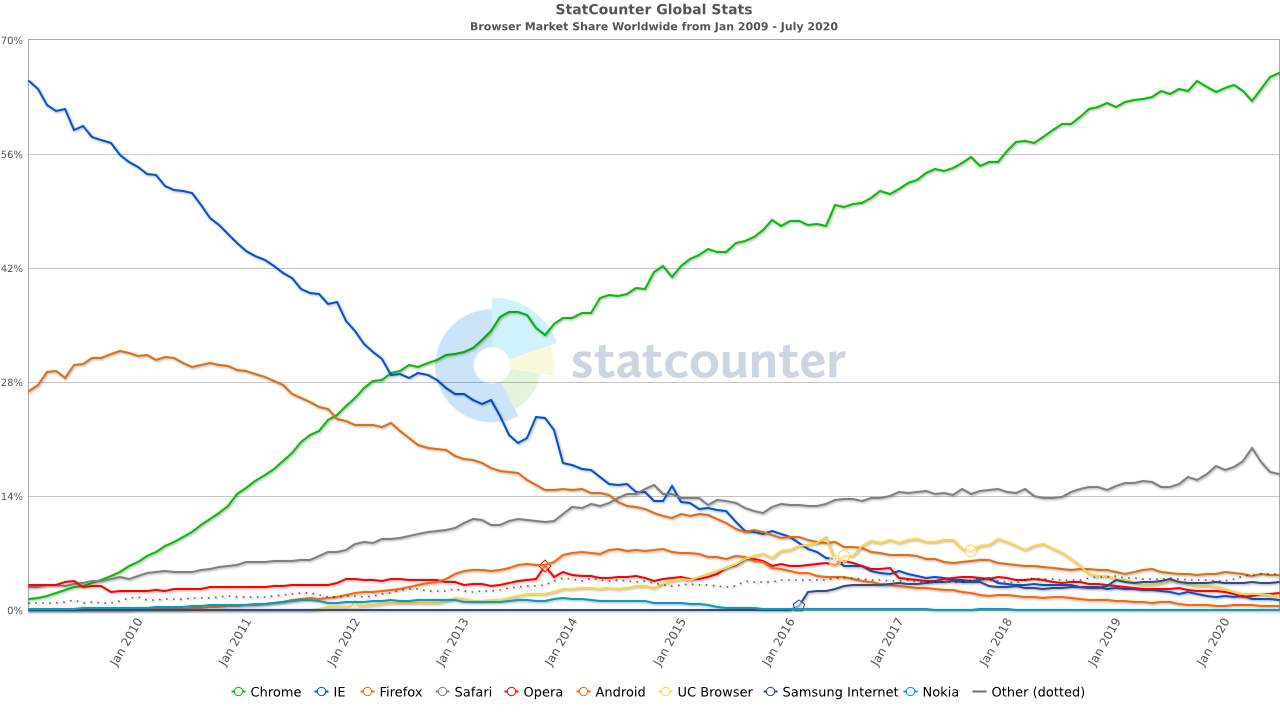

The platform side is what changed last week, when [Mozilla laid off 250 employees](https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2020/08/firefox-maker-mozilla-lays-off-250-workers-says-covid-19-lowered-revenue/) and indicated that it would affect Firefox development. Firefox wasn’t the #2 browser - that’s Safari, mainly because of the captive audience of iPhone and iPad users. But it was the most popular browser that people _chose_ to use.

_Chart from [statcounter](https://gs.statcounter.com/browser-market-share#monthly-200901-202007)_

The real winner is not just Chrome, but Chrome’s engine. One codebase, [KHTML](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/KHTML), split into [WebKit](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/WebKit) (Safari), and [Blink](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blink_(browser_engine)) (Chrome, Microsoft Edge, Opera, etc.)

This is a textbook monoculture. In one sense, it’s a victory for collaboration because nobody’s ‘wasting time’ on competing implementations and web developers can expect the same features and bugs across different browsers. But in a deeper way, it threatens one of the basic principles of how the web has evolved.

The web has evolved through a combination of _specifications_ and _implementations_. Organizations like the [WHATWG](https://whatwg.org/), [W3C](https://www.w3.org/), and [IETF](https://www.ietf.org/) have been collaboration spaces for independent developers, corporations, and academics to discuss potential new features of the web. Then, browsers would test those ideas out in a variety of implementations.

This was an interesting structural piece: it reassured us all that it was _possible_ to follow along, and that a multi-participant web was one of our goals. It was frustrating to pull up [caniuse](https://caniuse.com/) and see blank spots, but the idea was that different browsers may take the lead in some areas, but everyone catches up eventually. Chrome was not always the first to jump on features, or the first to optimize.

It’s slower to collaborate than to work alone, but it was beneficial in some ways that we’ve lost now. Chrome has been moving extremely fast, adding new specifications and ideas at a startling rate, and it’s becoming one of the hardest pieces of software to replicate.

Mike Healy I think [said it best](https://twitter.com/mike_hasarms/status/1296575224599556097):

> Do you think the web has almost ‘priced itself out of the market’ in terms of complexity if only 1-2 organisations are capable of building rendering engines for it?

Not only is it nearly impossible to build a new browser from scratch, once you have one the ongoing cost of keeping up with standards requires a full team of experts. Read Drew DeVault’s [Web browsers need to stop](https://drewdevault.com/2020/08/13/Web-browsers-need-to-stop.html) for that point, and keep reading all of Drew’s stuff.

What about Flow?Yep, there’s a [browser called Flow](https://www.ekioh.com/flow-browser/), which may exist and may support a full range of web standards. If it does exist, I’ll be very excited about it, but it has been teased for almost a year now without any concrete evidence, so it could equally be vaporware.

### The problem for creators

The web has gotten much harder to develop for.

The web has had about 25 years to grow, few opportunities to shrink, and is now surrounded by an extremely short-sighted culture that is an outgrowth of economic and career short-termism. There are lots of [ways to do anything](https://frankchimero.com/blog/2018/everything-easy/), and some of the most popular ways of building applications on the web are - in my opinion - [usually ghoulish overkill](https://macwright.com/2020/05/10/spa-fatigue.html).

The best way for folks to enter _web development_ in 2020 is to choose a niche, like [Vue.js](https://vuejs.org/) or [React](https://reactjs.org/), and hope that there’s a CSS and accessibility expert on their team.

For folks who just want to create a web page, who don’t want to enter an industry, there’s a baffling array of techniques, but all the simplest, probably-best ones are stigmatized. It’s easier to stumble into building your resume in React with GraphQL than it is to type some HTML in Notepad.

### The problem for consumers

We hope that all this innovation is _for the user_, but often it isn’t. Modern websites seem to be as large, slow, and buggy as they’ve ever been. Our computers are [barely getting faster](https://macwright.com/2019/11/15/something-is-wrong-with-computers.html) and our internet connection speeds are stagnating (don’t even _try_ to mention 5G). Webpage [size growth](https://www.pingdom.com/blog/webpages-are-getting-larger-every-year-and-heres-why-it-matters/) is outpacing it all.

The end result is that I no longer expect pages to be fast, even with [uBlock](https://github.com/gorhill/uBlock) installed in Firefox and a good local [fiber internet provider](https://sonic.net/).

I don’t want to lay all of the blame at _those web developers_, though. Here’s a story from an old job that I find kind of funny. We were collecting some data from user interactions to answer simple questions like “do people click to upload or do they drag & drop?” So we enabled [Segment](https://segment.com/), a tool that lets you add data-collection pipelines by including a single script. The problem, though, is that Segment offered a big page of on/off switches with hundreds of data providers & ad-tech companies on it. And, sure, enough, some folks closer to the business side started _clicking all those buttons_.

See, the problem with ads and data tracking is that _you can_, and who is going to say no? (In that instance, I said no, and added a [CSP](https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/HTTP/CSP) that would block new advertiser access at the page level.)

## Recreating simplicity

> You cannot get a simple system by adding simplicity to a complex system. - [Richard O’Keefe](https://erlang.org/pipermail/erlang-questions/2012-March/065087.html)

Where do we go from here? Some of the smartest folks out there have been [advocating for a major version revision](https://twitter.com/_developit/status/1296628134406692865) of the web.

_I am in no way qualified to speculate on a whole new web from scratch, but the [air quality](https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/21/us/california-wildfires.html) is scary so I’m skipping my run and it’s Saturday morning so here we are._

How do we make the web fun, participatory, and good?

My first thought is that there are two webs:

### The document web

There is the “document web”, like blogs, news, Wikipedia, Twitter, Facebook. This is basically the original vision of the web, as far as I can understand it (I was 2). Basically CSS, which we now think of as a way for designers to add brand identity and tweak pixel-perfect details, was instead mostly a way of making plain documents readable and letting the _readers_ of those documents customize how they looked. This attribute actually [survived for a while in Chrome, in the form of user stylesheets](https://twitter.com/autiomaa/status/1296755641164468224), and [still works in Firefox](https://davidwalsh.name/firefox-user-stylesheet). Though it’s going to be a rough ride in the current web which has basically thrown away [semantic HTML](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semantic_HTML) as an idea.

### The “application” web

Then there’s the “application web”. This started as _server_ applications, built with things like [Django](https://www.djangoproject.com/) and [Ruby on Rails](https://rubyonrails.org/) and before them a variety of technologies that will live forever in corporations, like [Java Servlets](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jakarta_Servlet).

[Backbone.js](https://backbonejs.org/) demonstrated that a lot of these applications could be moved into the browser, and then [React](https://reactjs.org/) and its many SPA-style competitors established a new order for the web – highly-interactive, quite complex, client-side applications.

### The war between the parts of the web

I posit that this dual-nature is part of what gives the web its magic. But it’s also a destructive force.

The magic is that a simple blog can be creative expression, can be beautifully interactive. This one isn’t, but I’m just saying - [it’s possible](https://www.typewolf.com/site-of-the-day).

The problem is that the “document web” is often plagued by application characteristics - it’s the JavaScript and animations and complexity that makes your average newspaper website an unmitigated disaster. Where document websites adopt application patterns they often accidentally sacrifice [accessibility](https://www.a11yproject.com/), performance, and [machine readability](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Web_scraping).

And the “application web” is plagued by the document characteristics - interactive applications are going to great lengths to avoid most of the essential characteristics of HTML & CSS and just use them as raw materials - avoiding writing any HTML directly at all, avoiding [writing any CSS directly at all](https://mxstbr.com/thoughts/css-in-js), avoiding [default animation features](https://www.react-spring.io/), replacing [page-based navigation with something that looks like it but works completely differently](https://reactrouter.com/). The application web uses [JSX](https://reactjs.org/docs/introducing-jsx.html), not HTML, and would like that in the browser itself, or [Svelte](https://svelte.dev/), instead of JavaScript, and would like that too.

When I read blog posts from ‘traditional web developers’ who are mad that HTML & CSS aren’t enough anymore and that everything is complicated –I think this is largely that the application stack for building websites has replaced the document stack in a lot of places. Where we would use Jekyll or server-side rendering, we now use React or Vue.js. There are advantages to that, but for a lot of minimally-interactive websites, it’s throwing away decades worth of knowledge in exchange for certain performance perks that might not even matter.

The appeal of social networks is partly because they let us create _documents_ without thinking about web technology, and they provide guarantees around performance, accessibility, and polish that otherwise would take up our time. You don’t have to think about whether your last Facebook post will load quickly on your friend’s phone or whether your Instagram post will be correctly cropped and resized in the timeline - those things are taken care of.

To some extent, this doesn’t _need_ to be something that only social networks provide, though: standards like [RSS](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RSS) and services like [Instapaper](https://www.instapaper.com/) show that pleasing formatting and distribution can be done at the _platform level_ and be provided on top of existing vanilla websites.

These are not absolutes.Yeah, I can hear it now: but these categories are not precise! There are plenty of applications that dont sacrifice performance or accessibility, and plenty of document websites that genuinely need interactivity, and plenty of web developers who are just using the platform - vanilla JavaScript or web components - and who dont need or want the web to be different. All categories that you draw out of real-world environments are going to be imprecise. Thats how all non-technical thinking works: the question isnt whether theyre perfect, its whether theyre useful for advancing the discussion.

## Document web 2.0

A unified theory of a new web that had just enough application characteristics and enough document characteristics to provide the sorts of hybrid interactive documents that we see today - now that would be cool. But the path to a splintered web is clearer and is what I’m thinking of first, so here’s some of that.

- Rule #1 is _don’t make a subset_. If the replacement for the web is just whatever features were in Firefox 10 years ago, it’s not going to be a compelling vision.

- Rule #2 is _don’t make it compatible_. If the replacement web lives alongside, undifferentiated from the current web, then you’ll never actually reduce complexity because replacement web browsers will still support everything, and people won’t be encouraged to leave the old web.

- Rule #3 is _make it better for everyone_. There should be a perk for everyone in the ecosystem: people making pages, people reading them, and people making the technology for them to be readable.

Okay, so let’s say we’re creating a new document web.

**First, you need a minimal, standardized markup language for sending documents around.** You might want to start with a [lightweight markup language](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lightweight_markup_language), which will ironically be geared toward generating HTML. Markdown’s strict specified variation, [Commonmark](https://spec.commonmark.org/), seems like a pretty decent choice. That’s the language I’ve written all my blog posts in, and the most popular language in its family. There are lots of great parsers and a big ecosystem of tools for Markdown.

**Then, you need a browser.** Mozilla has been working on a brand new browser for a while - [Servo](https://servo.org/). That team got laid off last week, which sucks. That project includes standalone Rust crates for [font rendering](https://github.com/servo/pathfinder), and there’s a [world-class Rust Markdown implementation](https://github.com/raphlinus/pulldown-cmark), and a growing set of [amazing application frameworks](https://github.com/linebender/druid). Could you build a pure-Markdown-browsing browser that goes straight through this pipeline? Maybe?

I think this combination would bring speed back, in a huge way. You could get a page on the screen in a fraction of the time of the web. The memory consumption could be tiny. It would be incredibly accessible, by default. You could make great-looking default stylesheets and share alternative user stylesheets. With dramatically limited scope, you could port it to all kinds of devices.

And, maybe most importantly, what would website editing tools look like? They could be _way_ simpler.

What could aggregation look like? If web pages were more like documents than applications, we wouldn’t need RSS - websites would have an index that points to documents and a ‘reader’ could aggregate actual webpages by default.

We could link between the webs by using something like dat’s [well-known file](https://beakerbrowser.com/docs/guides/use-a-domain-name-with-dat#well-knowndat), or using the [Accept header](https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/HTTP/Headers/Accept) to create a browser that can accept HTML but prefers lightweight pages.

## Application web 2.0

I feel like every time I mention something about the web, the automatic response is that WebAssembly might fix it. Maybe?

I don’t know. WebAssembly _is_ pretty great, but should web applications just be rendered to a canvas, and every application brings its own graphics toolkit? Do we really want anti-aliasing differences between web applications? Applications-in-containers is a thing - look at [Qubes](https://www.qubes-os.org/) - but it’s not really something that users should want. Anyone who has used Blender or Inkscape on a mac has some idea of how this goes.

Or is WebAssembly the new ‘core’ and we still render UIs with HTML? Or… create a shared linked library that WebAssembly apps can use that works roughly like [SwiftUI](https://developer.apple.com/documentation/swiftui), offering application-friendly layout conventions like constraints instead of document-centric ideas like line heights and floats?

The problem with imagining the application web is that it’s pretty expansive.

The worse the ‘Mac App Store’ and ‘Windows App Store’ and ’App Store’ and ’Play Store’ get, the bigger a cut those monopolies demand, the more it costs to be a Mac or Windows developer, the more that applications get pushed to the web. Sure, some applications are _better_ on the web. But a lot are just there because it’s the only place left where you can easily, cheaply, and freely share or sell a product.

There was a time when we could install applications, give some sort of explicit agreement that something would run on our computers and use our hardware. That time is ending, and web pages now have rather complex ways of getting at everything from webcams to files, game controllers, audio synthesis, cryptography, and everything else that was once the domain of `.exe` and `.app`s. This is empowering, sure, but is quite an unusual situation.

### Who’s working on this?

- [Beaker Browser](https://beakerbrowser.com/) is partly a reinvention of the _internet_–it’s the simplest [way to use dat for decentralization](https://macwright.com/2017/07/20/decentralize-your-website.html), but they’re also experimenting with new kinds of documents and ways of authoring.

- [Project Gemini](https://gemini.circumlunar.space/) is a really interesting, distinctly retro-flavored web alternative. (via [Jesse](https://jklabs.net/))

- I’ve been pretty inspired by [taizen](https://github.com/NerdyPepper/taizen), a command-line based Wikipedia browser. It shows how a text-first experience can be really fun.

### What do you think?

There are a lot of other ways to look at and solve this problem. I think it _is_ a problem, for everyone except Google. The idea of a web browser being something we can _comprehend_, of a web page being something that _more people can make_, feels exciting to me.

The markdown-centric approach feels very doable. I think the clearest rebuttal is that it ‘sucks all the fun out of the web,’ and there’s some truth to that. But the early web wasn’t fun in many conventional ways - you couldn’t quite create art there, or use it as much more than a way of sharing documents. But it was fun as heck, because sharing is fun and it was simple and flexible in some cool ways. So the key is to discover the small things that unlock the possibilities in this plan, if they’re there. Or find a different plan with ‘just enough fun.’

Social networks are universally _more restrictive_ than web pages but also _more fun_ in significant ways, chief amongst them being that more people can participate. What if the rest of the web have that simplicity and immediacy, but without the centralization? What if we could start over?